188

188

Yellow gold, painted wood

Signed Nevelson

2.50 x 2 in

estimate: $5,000–7,000

result: $12,600

follow artist

As consummate patrons of the arts, Acey and Bill Wolgin did not just live with the art that they collected—they lived alongside the artists who made it. Through their generous support of both individual artists as well as institutions they cherished, the Wolgins became widely celebrated collectors known for their friendships with artists—including Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein, Arman, and Robert Rauschenberg—that were sustained, not least, by legendary parties thrown at their Philadelphia apartment.

Bill Wolgin, who practiced as a urologist, met Acey through her brother with whom he attended medical school. The pair married and made strong roots in Philadelphia—indeed, the Wolgins may be credited for having a significant role in elevating the City of Brotherly Love to the cultural destination that it is today. In the 1960s, Acey was a founding member of the Arts Council at the Young Women’s Hebrew Association, which helped spark the city’s contemporary art scene. In 1974, Acey became one of the first women elected to the board of the Philadelphia Art Museum, where she served as a trustee and trustee emeritus for the rest of her life. When Robert Indiana’s LOVE stamp was released at that museum, Acey’s birthday party doubled as the event after-party. Among the attendees was the artist Arman, who absconded with a piece of the LOVE stamp-themed cake in order to seal it in resin.

The Wolgins would later relocate to Boca Raton, where they became actively involved in the Boca Raton Museum of Art and eventually funded the Wolgin Education Center. After returning to Philadelphia, Bill Wolgin would become involved in the Woodmere Art Museum as a trustee, helping to guide the institution’s expansion. Works from the Wolgin Collection are now held in all three of the institutions where they became involved, including Yves Klein’s Portrait Relief I: Arman at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Fletcher Benton’s Donut with Balls and Half Moon at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, and a group of large-scale sculptures by Sam Maitin at the Woodmere Art Museum.

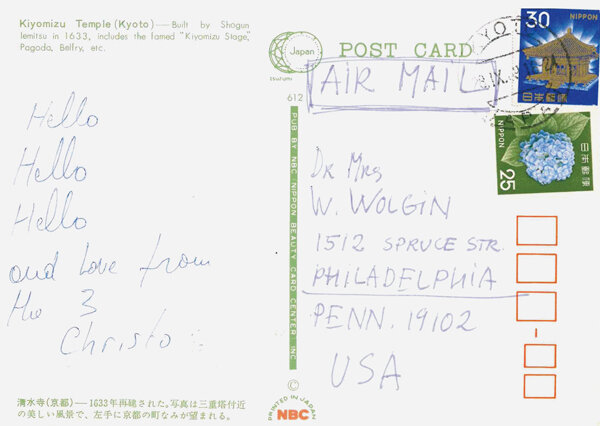

Surrounded by his parents’ collection from a young age, Richard Wolgin recalls meeting many of the artists whose works he knew intimately—especially memorable was the flaming red hair of Jeanne-Claude when she and Christo dropped in one weekend. (When they weren’t celebrating together, the Wolgins kept correspondences with many of their artist-friends, who sent postcards and, sometimes, drawings.) As kids, Richard and his sister would, naturally, delight in playing with one of Harry Bertoia’s sound sculptures. When Richard was twelve years old, Acey gave him his first work: Roy Lichtenstein’s CRAK!, which he affixed to his bedroom wall with thumb tacks—inadvertently bringing the work back into the realm of mass media and pop cultural detritus that so inspired Lichtenstein.

The works featured in The Acey and Bill Wolgin Collection represent a life lived through, and for, art—“It’s not just buying something to hang on the wall,” says Richard, “it’s a piece of their lives, that are now part of our lives.”

Louise Nevelson 1899–1988

Louise Nevelson is best known for her large-scale, monochromatic, painted wood assemblages. She was a harbinger of feminist and installation art that rose to prominence in America in the mid-twentieth century. Her sculptures reflect her interior life, women’s roles in society, the urban landscape, personal symbolism and spirituality. Nevelson was also well-known for her cultivated style and no-nonsense personality, both of which helped sustain her tenacious confidence over the course of five decades, as the art world came around to celebrating her work and its impact.

Louise Nevelson was born Leah Berliawsky in 1899 in a part of Ukraine that is now Russia. In 1905 her family immigrated to Rockland, Maine to escape the persecution the Jewish community suffered under Tsarist Russia. Nevelson had artistic aspirations from an early age and in 1920, after marrying the son of a wealthy businessman, she and her husband moved to New York City. She gave birth to a son in 1922 and began taking classes at the Arts Students League in 1928. Finding it difficult to balance her family and her ambitions, she and her husband divorced in 1931 and she traveled to Munich to study under Hans Hofmann. The following year, Hofmann immigrated to America and Nevelson followed suit, returning to New York. She once again studied at the Art Students League, working under George Grosz and Chaim Gross and also worked for the Works Progress Administration, where she encountered many of the era’s soon-to-be-famous artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

Nevelson’s work began attracting attention in the early 1940s, though financial success belied her early efforts. Being a woman, along with creating large, ambitious works made from refuse wood, contributed to the lack of initial fanfare around her work. In the 1950s she began being showing at respected galleries in New York, including Martha Jackson Gallery and Pace Gallery (who still represents her work today) and her work was critically favored, but not fully embraced or understood by the art market. In 1959, Nevelson’s Dawn’s Wedding Feast was shown in the Museum of Modern Art’s seminal exhibition of avant-garde contemporary art, 16 Americans. Also included in that show were works by Jasper Johns , Frank Stella and Robert Rauschenberg. Nevelson was working within a similar mode as many of the era’s abstract expressionist painters—creating work out of an inner, emotional, self-guided searching, rather than from any obvious relation with culture or nature. Her assemblages, though made out of salvaged, mismatched wood, are unified and elegant in their depth and interior rationality. Dense and lyrical, these works speak to celestial bodies, personal myth-making, and psychological landscapes.

The Whitney Museum of American Art held Nevelson’s first retrospective in 1967 and in the 1970s, when Nevelson was in her seventies, she began receiving commissions for large, outdoor sculptures, which inspired her to work with new materials such as steel. Nevelson died in 1988 in New York, leaving behind a legacy of sustained creative persistence and vision that influenced scores of young artists that came after her.

Auction Results Louise Nevelson