198

198

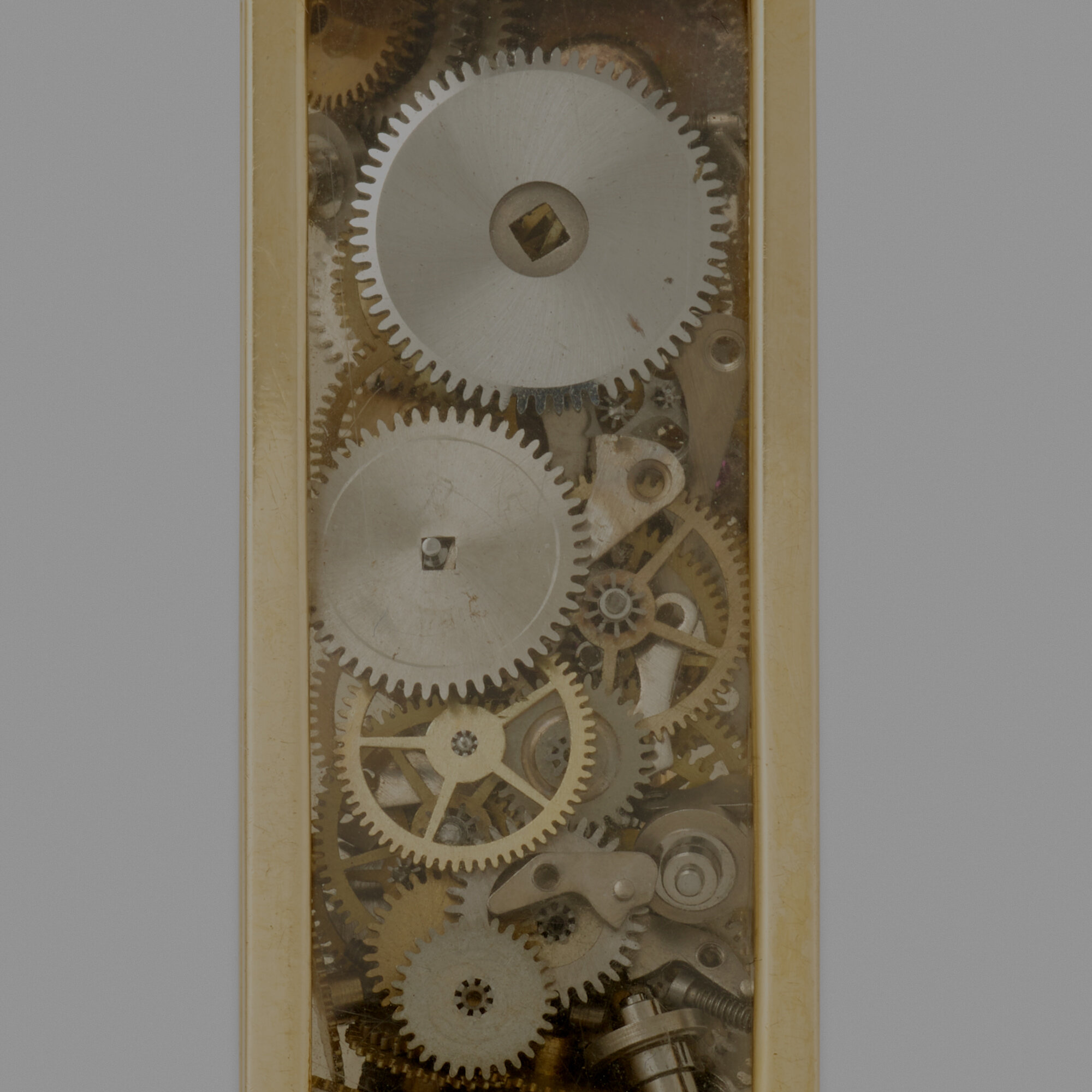

Yellow gold

Signed Arman to each violin

Inner circ. 14 in, each pendant 2.50 x 1 in;

Sold with copy of Notes in Hand by Arman

estimate: $7,000–9,000

result: $4,410

follow artist

I remain a sculptor and a painter whose ambition, before making a speech about ourselves or our civilization, is to produce a work of art.

Arman

As consummate patrons of the arts, Acey and Bill Wolgin did not just live with the art that they collected—they lived alongside the artists who made it. Through their generous support of both individual artists as well as institutions they cherished, the Wolgins became widely celebrated collectors known for their friendships with artists—including Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein, Arman, and Robert Rauschenberg—that were sustained, not least, by legendary parties thrown at their Philadelphia apartment.

Bill Wolgin, who practiced as a urologist, met Acey through her brother with whom he attended medical school. The pair married and made strong roots in Philadelphia—indeed, the Wolgins may be credited for having a significant role in elevating the City of Brotherly Love to the cultural destination that it is today. In the 1960s, Acey was a founding member of the Arts Council at the Young Women’s Hebrew Association, which helped spark the city’s contemporary art scene. In 1974, Acey became one of the first women elected to the board of the Philadelphia Art Museum, where she served as a trustee and trustee emeritus for the rest of her life. When Robert Indiana’s LOVE stamp was released at that museum, Acey’s birthday party doubled as the event after-party. Among the attendees was the artist Arman, who absconded with a piece of the LOVE stamp-themed cake in order to seal it in resin.

The Wolgins would later relocate to Boca Raton, where they became actively involved in the Boca Raton Museum of Art and eventually funded the Wolgin Education Center. After returning to Philadelphia, Bill Wolgin would become involved in the Woodmere Art Museum as a trustee, helping to guide the institution’s expansion. Works from the Wolgin Collection are now held in all three of the institutions where they became involved, including Yves Klein’s Portrait Relief I: Arman at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Fletcher Benton’s Donut with Balls and Half Moon at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, and a group of large-scale sculptures by Sam Maitin at the Woodmere Art Museum.

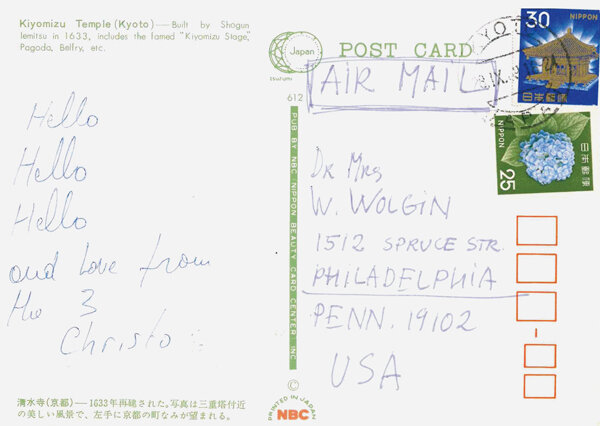

Surrounded by his parents’ collection from a young age, Richard Wolgin recalls meeting many of the artists whose works he knew intimately—especially memorable was the flaming red hair of Jeanne-Claude when she and Christo dropped in one weekend. (When they weren’t celebrating together, the Wolgins kept correspondences with many of their artist-friends, who sent postcards and, sometimes, drawings.) As kids, Richard and his sister would, naturally, delight in playing with one of Harry Bertoia’s sound sculptures. When Richard was twelve years old, Acey gave him his first work: Roy Lichtenstein’s CRAK!, which he affixed to his bedroom wall with thumb tacks—inadvertently bringing the work back into the realm of mass media and pop cultural detritus that so inspired Lichtenstein.

The works featured in The Acey and Bill Wolgin Collection represent a life lived through, and for, art—“It’s not just buying something to hang on the wall,” says Richard, “it’s a piece of their lives, that are now part of our lives.”

Arman 1928–2005

Born in 1928 in Nice, France, Armand Pierre Fernandez was one of the most prolific and innovative artists working in the French Pop Art movement. Arman began his formal training at the Ecole Nationale des Arts Décoratif in Nice in 1946, but then moved to Paris study at the Ecole du Louvre. In 1947, he forged a friendship with fellow artist Yves Klein, and the two soon began to create art that responded to the post-war condition. Arman’s art dealt with the Duchampian notion of the ready-made, as he employed commodity objects to question the ideas of exuberant mass-production. In 1960, he joined Klein to found the French artistic group Nouveau Réalisme, which sought to find “new ways of looking at the real.”

In 1961, Arman moved to New York, where he took up residence in the infamous Chelsea Hotel. Arman felt that in coming to New York, he was “in the center of [his] dreams, vitrines of vitrines, a profusion of windowed crystals on the rock of Manhattan.” He became friends with fellow Pop Artist Andy Warhol, who began to collect Arman’s work and in 1964, Arman was featured in Warhol’s film Dinner at Daley's. Arman was granted American citizenship in 1972. In 1982, he constructed his formative sculpture Long Term Parking, which consisted of an obelisk-like pile of cars encased in concrete. In 1991, the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York honored Arman with the first U.S. retrospective of his works. Arman died in 2005, but he left behind a legacy of art that played with the conventions of consumer commodities. His works are housed in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the Tate Museum in London, among many others.